- Paving

- Electrical Engineering and Telecoms Infrastructure

- Civil Engineering, Mining, Railway, Building and Plumbing Products

- Curbs / Kerbs

- Landscaping, Streetscaping, Gardening products

- Moulds

- Pizza Oven Kit

- Avalon range

- Builders' and Plumbers' Products

- Benches and Seats

- Concrete Tables

- Grass Blocks

- Litter/Refuse Bins

- Pots and planters (Discontinued)

- Tree rings

- Bollards and Barriers

- Stone Cellar Blocks

- Water features (Discontinued)

CIVIL ENGINEERS

INTRODUCTION TO PERMEABLE PAVING

The Problem: Rainwater versus Pavement

Illustrative question: Which one causes the greater stormwater problem: 1) A sports field or 2) A paved parking lot the size of the sports field?

The problem in urban areas is that more and more hard surfaces (roofs and pavements) are built that reduce natural infiltration. As seen in the sports field example: Natural infiltration absorbs the first amount of water and only a sizable storm will produce excess runoff. It works like an attenuation dam. The excess has to be handled but it is much less than in the case of hard surfaces.

Aside from stormwater, impervious paving has other environmental consequences including:

- The local depletion of groundwater;

- The difficulty in getting trees to grow within and around paved areas: Roots are denied rainwater and root conditions are anoxic. Irrigation is a partial solution.

- Hydrocarbons i.e. oil spillage and tyre rubber is washed straight into the nearest waterway with every rainfall.

The extent of the problem in built-up areas is huge. In countries like the USA and South Africa that use road vehicles as a primary means of transport, pavements occupy twice the surface area of buildings. Of all the physical features of cities paving is the most influential. It dominates the quality of urban environments. It is responsible for essentially two thirds of the excess runoff with all its consequences as mentioned above (ref 1).

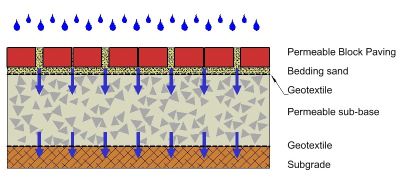

Permeable paving, as opposed to ordinary paving, allows the free passage of rainwater through it into the ground. It also allows air to pass through the provided voids. This ensures that the ground breathes naturally by thermal action, supplying oxygen to roots and aerobic bacteria.

Permeable paving or Permeable Concrete Block Paving (PCBP) is not simply a standard road foundation with permeable paving on top. It is a design philosophy which, when using a range of techniques in sequence, is known as a management train. PCBP manages surface water by attenuation and filtration with the aim of replicating, as closely as possible, the natural drainage from the site before development (ref 2). The two basic components of PCBP are porous paving blocks and a porous road foundation.

In the design philosophy PCBP is used in the place of elaborate stormwater systems including catchpits, massive pipes, canals and outlet structures. All or part of the surface is made permeable, and the water is allowed to infiltrate. While collecting under the surface it absorbs the flood, infiltrates the ground and the (much reduced) excess is drained away.

Three broad systems depending on ground conditions can be identified (ref 2):

System A – Full Infiltration

Suitable for a subgrade with good permeability. This system allows all the water falling onto the pavement to infiltrate through the constructed layers. Some temporary water retention may occur but no water is discarded into a drainage system. This system is particularly economical.

System B – Partial Infiltration

Used where the subgrade is not able to absorb all the water. A fixed amount of water is allowed to infiltrate – which often represents a large percentage of the rainfall. Outlet pipes are connected to the permeable sub-base, which allow excess water to be drained to other devices such as swales, ponds, watercourses or sewers.

System C – No Infiltration

Applicable where the existing subgrade permeability is poor or contains pollutants. System C allows for the complete capture of the water. By isolating the porous sub-base from the surrounding subgrage by means of a flexible membrane it acts as a storage tank. Outlet pipes are connected through the membrane to transmit the water as is appropriate.

The advantages of this system are: 1) attenuation and much smaller drainage pipes and 2) isolation where there is risk of contamination. In the arid parts of Australia, a similar system is used for collecting and storing rainwater. It is then used locally for irrigation or in water features.

Experience and Information

PCBP has been around throughout the UK, Europe, especially Germany, Australia, the USA and other parts of the world for decades. The functionality and economy of PCBP is well proven in those countries. There is a wealth of information and experience available so that design and implementation is no longer experimental but a specifiable practice.

Dr. Brian Skackel (ref 3) of the University of New South Wales, being a renowned specialist on segmental paving design has published widely on PCBP. He also developed a computer aided design program for segmental paving that includes PCBP, which has been in use for years. These programmes, called LockPave and PermPave are distributed by the Concrete Manufacturers Association of South Africa.

Download link: www.cma.org.za/. Look under paving technical information or enquire with the CMA

Other sources of information:

www.paving.org.uk/permeable.php - comprehensive information, design guidelines;

www.sept.org - the latest technical know-how on segmental paving in general and PCBP, technical papers etc.

www.cma.org.za/ – CMA Publications on Paving including a handy Introduction to PCBP.

Valuable work was done by Dr. Soenke Borgwardt on the Long Term In-Situ Infiltration Performance of Permeable Paving.

Economy of PCBP

Although it is not obvious at first, permeable paving is more economical than conventional segmental paving with its stormwater system. Please consider the following:

- The cost of the paving blocks whether permeable or conventional should be in the same order. At first the permeable type may be somewhat more expensive to cover manufacturers’ development costs but it should completely level out after a few years. Graded filling and bedding sand (no fines) instead of plain sand will have a small effect on cost.

- The base and subbase layers for PCBP will be more expensive because of the use of crushed stone instead of natural gravel.

- There is however a huge saving when it comes to stormwater management. Depending on the ground conditions, PCBP may need no additional stormwater measures as the rainwater filters directly into the ground. When the ground is impervious, it will require only small diameter drainage pipes comparable to domestic sewers. This is possible because 1) the peak flood is absorbed and 2) the pipes cannot block as the water is already filtered, containing no grit or debris. If this is compared with a system of massive pipes, attenuation measures, catch pits, grids, kerb inlets, manholes and outlet structures, the saving is obvious.

- Not all of the paving and sub-layers need to be permeable. At the Grand Parade in Cape Town, a pre-world cup project used PCBP only for the bottom quarter of the 10 000 m2 of new paving. The higher-up 75% is conventional Concrete Block Paving (CBP). The CBP surface drains unto the PCBP, which absorbs all of the runoff and disposes of it.

During rain, the difference between the wet and dry surfaces is obvious.

Picture: CMA. Blocks by Inca ConcreteIn the same way road shoulders or roadside parking bays may be designed as permeable while the traffic-carrying roadway is conventional. This can bring about a further saving.

- The cost of damage to the environment by impervious paving is more difficult to quantify but should be bourne in mind as an added benefit.

Strength versus Permeability

Segmental Paving as a load carrying surface, relies on effective interlock to spread the load as it is transmitted downward. Interlock is enhanced by the shape of the block and equally so by the effectiveness of tightly filled joints. It stands to reason, and it has been proven by Dr. Shackel (ref 3) that load bearing capacity is reduced as the friction transmitted by the joints are reduced by open or loose joints.

Permeability in PCBP is achieved by holes in the blocks or in the pattern of laying, and by wider joints. Both the holes and the joints are filled with an open-graded sand free of fines.

Clearly wider joints with less well graded filler sand will reduce friction and therefore interlock. On the other hand tight joints that are filled with sand containing fines will not allow flow-through. It has been found though that carefully designed PCBP blocks with holes and good interlock together with selected filler sand of the right specification are very successful. Such a pavement is effective both as a traffic carrier and a permeable surface.

Vanstone's Offer:

Interlocking type concrete block pavers are by far the best performers for load bearing capacity. Vanstone's Aqualock Pavers are specially designed to have strong interlock and openings to let the water through.

Vanstone now offers three new Permeable Concrete Block Pavers: The Aqualock Pavers in 60mm and 80mm thick and the Aqua Random Pavers that are 50mm thick.

References:

- Bruce K. Ferguson: Porous Pavements, CRC Press 2005

- Concrete Manufacturers Association (South Africa): An Introduction to Permeable Concrete Block Paving

- Prof. Brian Shackel BE Sheff, MEngSc PhD UNSW, CPEng, FIEAust Email: [email protected]

Read Also:

Important Landscape Architects' and Architects' perspectives

> View Vanstone's "Aqua Range" of Permeable Concrete Block Pavers